Democracy Education: About - Through - For

Democracy in school includes knowledge about, learning through experience and also learning for a democratic, active citizenship.

Topics

Democracy education includes knowledge about democracy and learning through experiencing democracy and democratic processes in school. The goal of democracy learning is empowerment; education occurs so that students can act and participate as democratic citizens.

Various dimensions of democracy learning

Building democratic competence as a counterbalance to prejudice and hatred involves more than providing knowledge about democratic processes and values. Democracy learning encompasses various approaches to learning, reflecting different dimensions of understanding what democracy really is or is about.

How to facilitate democracy becoming not just a theoretical and distant concept for students but something connected to their own lifeworld? How to ensure that democratic citizenship is both experienced and practiced in everyday life? The core curriculum states that "The school shall provide students with the opportunity to participate and learn what democracy means in practice." Thus, democracy learning in schools should be about much more than social studies instruction.

“

How to facilitate democracy becoming not just a theoretical and distant concept for students but something that connects to their own lifeworld?

Different understandings of democracy emphasize different dimensions of democracy, pointing to different prerequisites for democratic participation (see Understandings of Democracy and Democracy Learning). Thus, they also refer to different dimensions of the learning process, which can be described as learning 'about, through, and for democracy.'

Learning about democracy

"Learning about" refers to the knowledge and understanding of organization and social institutions necessary for students to participate in democracy in the future by voting and using democratic institutions. Students need to learn about democratic institutions and procedures to be prepared for democratic participation. This dimension can be linked to the idea of representative democracy, where citizens have both rights and duties. From this perspective, teaching about the structure of democracy becomes the most important component of democracy education.

“Students need to learn about democratic institutions and procedures to be prepared for democratic participation.

Learning through democracy

"Learning through" refers to the idea that democracy is not just something learned in theory but through experiencing, practicing, and internalizing democratic processes and values in a concrete context and as a concrete practice. This dimension can be linked to the participatory democratic perspective, which emphasizes individuals' participation in processes leading to political decisions, in addition to voting in elections. This perspective underscores "that participation is a condition of life, that is, a condition for a good life"

“"Learning through" refers to the idea that democracy is not just something learned in theory but through experiencing, practicing, and internalizing democratic processes and values in a concrete context and as a concrete practice.

"Learning through" is also closely related to the idea that democracy is a way of life, a "way of living" that must permeate relationships and interactions in all social forms and institutions From this perspective, democracy learning must not only provide knowledge about the functions of democracy but also competence for participation in the broad sense, which presupposes learning through participating in democratic processes and experiencing democratic interaction in the school environment.

"Learning through" thus points to the process dimension of learning. The methods used, the communication that takes place, and the relationships built should be consistent with the principles and values to be conveyed. This dimension of a learning process is crucial for the emotional dimension of competence development.

"Learning through" thus involves allowing for students' participation and involvement in everyday school life. The core curriculum (1.6) clearly indicate such an understanding of democracy learning: "Students should experience that they are listened to in their everyday school life, that they have real influence, and that they can influence what concerns them. They should gain experience with and practice various forms of democratic participation and involvement, both in the daily work of the subjects and through, for example, student councils and other council bodies."

“The methods used, the communication that takes place, and the relationships built should be consistent with the principles and values to be conveyed.

Learning for democracy

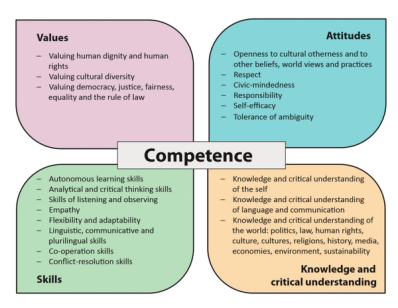

"Learning for democracy" points to empowerment and the action-oriented dimension of competence development; the learning process should equip students for concrete action, or, to use the words in the Council of Europe's competency framework, "for active participation in democratic and multicultural societies" Such participation requires an interplay between knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes. Thus, democracy learning must provide students with an experiential background that involves not only necessary understanding and practical abilities but also motivation for engagement and participation.

“Democracy learning must provide students with an experiential background that involves not only understanding and practical abilities but also motivation for engagement and participation.

emphasizes in her operationalization of the three dimensions "about, for, and through democratic participation" that values and attitudes are central to learning for democracy. The important point here lies in the significance of values and attitudes as guiding, making competence democratic competence.

History has shown that both knowledge and skills can be used for inhumane actions. However, learning for democracy involves more than the development of attitudes and values – a broad range of skills, knowledge, and attitudes create preparedness for democratic action.

Learning for democracy involves more than the development of attitudes and values – a broad range of skills, knowledge, and attitudes create preparedness for democratic action.

There are nuances in interpretations of the various dimensions of democracy learning among professionals in the field of democracy, but there is agreement on the basic perspective: Democracy learning has both a process-oriented and an action-oriented dimension. Knowledge is not enough. Moral insight can never be acquired purely theoretically; it can only be developed through experience.

“Knowledge is not enough. Moral insight can never be acquired purely theoretically; it can only be developed through experience.

About, for, and through in a Dembra perspective

In a Dembra perspective, i.e., in light of the problems of prejudice and group hostility, it is evident that all three dimensions of democracy learning must be incorporated into the school's preventive work. Knowledge and critical understanding (learning about) are and remain crucial counterbalances to misinformation, fake news, and propaganda. The process and experiential dimension (learning through) touch on the depth dimension of attitudes and values. Prejudices are learned and "unlearned" in social relationships. Therefore, experiences of equal interaction and inclusion in a school context can contribute to building democratic reflexes against prejudice and hatred.

“Experiences of equal interaction and inclusion in a school context can contribute to building democratic reflexes against prejudice and hatred.

Finally, dealing with action competence in the face of inequality and discrimination also requires competence for change. Here, knowledge and skills need to be mobilized, and there needs to be an attitude-based motivation to participate in processes aimed at creating a more equal and just society – a society where neither skin color, ability, nor sexual orientation should be decisive for the opportunities to become a fully-fledged and equal participant in society.

Democracy and human rights learning

The model for democracy learning used in Dembra is developed from a similar model used in the field of human rights education. In the UN Declaration on Human Rights Education Article 2, learning "about, through, and for human rights" is defined as central dimensions in an empowering approach to learning:

Human rights education and training encompass:

- a: Education about human rights, which includes providing knowledge and understanding of human rights norms and principles, the values that underpin them, and the mechanisms for their protection;

- b: Education through human rights, which includes learning and teaching in a way that respects the rights of both educators and learners;

- c: Education for human rights, which includes empowering persons to enjoy and exercise their rights and to respect and uphold the rights of others.

These points are, as we see, directly transferable to the field of democracy education. Collectively, they indicate that human rights education, as well as democracy education, has both a process-oriented and an action-oriented dimension. Human rights must be experienced in practice to become an integrated part of an individual's values and preparedness for action.

“Work on human rights is closely connected to democracy education, as these rights specify what respect for human dignity and equality means in practice.

Human rights are the foundation of democracy. And although human rights, formally, primarily concern the state's responsibility to safeguard the rights of citizens, the responsibility to maintain thinking and actions that build respect for human dignity lies on each of us, in our everyday behaviors. As with democracy, respect for human rights is an ideal that must continually be realized through the actions of individuals in the social space.

Democracy education – the concern of the school as a whole

The various dimensions of democracy education point to the entire school's work. A central insight in research on school-based competence development is that there is no contradiction between thinking about subjects/instruction and a school-wide perspective – neither when it comes to reading and writing skills nor when the school's preventive work is formulated . Facilitating democracy education, therefore, means thinking about the entire school as an arena for democratic formation (see A democratic school culture).

“Facilitating democracy education means thinking about the entire school as an arena for democratic formation.

The understanding of learning about, through, and for democracy emphasizes that attitudes such as prejudices and group hostility can only be effectively countered through reflective and empowering approaches, both in subject instruction and other types of interaction in school. Knowledge about prejudices and skills such as critical thinking and reflection can be practiced in all subjects.

Learning through also extends beyond the instructional context and towards all situations that arise in a school day where prejudices are expressed and where offenses occur. Both prevention and handling of such situations are essential for students' experience of what democratic interaction means in practice.

emphasizes the connection between democracy and inclusion, both concerning the type of competence needed for participation in democracy and for living together in a culturally diverse society. The same is also emphasized in the Council of Europe's Competence Framework "Competences for Democratic Culture." Again, this points towards a holistic approach where the entire school functions as a democratic learning and interaction context that unites learning about, through, and for.

Literature:

Biseth, Heidi & Madsen, Janne (red.) (2014). Må vi snakke om Demokrati? Om demokratisk praksis i skolen. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Dewey, J. (1937): Education and Social Change.

Europaråd (2018) CDC and building resillience to radicalization leading to violent extremism and terrorism In: Reference framework of competences for democratic culture. Volume 3: Guidance for implementation, s. 101.123

http://rm.coe.int/prems-008518-gbr-2508-reference-framework-of-competences-vol-3-8575-co/16807bc66e

Lenz, C. (2020) Demokrati og medborgerskap i skolen. Pedlex

OHCHR (2010) United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Education and Training.

https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Education/Training/Pages/UNDHREducationTraining.aspx

Postholm, May Britt, Dahl, Thomas, Engvik, Gunnar, Fjørtoft, Henning, Irgens, Eirik J., Sandvik Lise Vikan & Wæge, Kjersti (2014). En gavepakke til ungdomstrinnet? En undersøkelse av den skolebaserte kompetanseutviklingen på ungdomstrinnet i piloten 2012/2013. Trondheim: Akademika.

Teaching plan on the same topic

- Teaching session45 - 59 min

How Can Individuals Influence Politics and Society?

Radicalization and Violent ExtremismDemocracy, Citizenship and Empowerment - Teaching session75 - 90 min

Norwegianness in Plural

Identity, Diversity and Belonging - Teaching session45 - 60 min

Favorite Prejudices

Prejudice and Group Thinking