Professional Competence and Professional Ethics

Topics

In the face of societal challenges related to racism, prejudices, group hostility, and hatred, teachers need both knowledge and tools to handle and prevent these issues. Working with complex group dynamics requires more than just subject knowledge; it requires pedagogical tact and discretion. No recipe can be given, but insight into the topics and ethical reflection can equip teachers to handle ethical dilemmas and daily challenges in teaching wisely and ethically.

Professional Ethics

Teachers are committed to the school's values and societal mandate, as expressed in the objects clause. Central to the value system is the dignity and equality of every individual. The overarching section elaborates on this view of humanity as a pedagogical commitment: Each student should experience recognition and care, even in cases where he or she makes "unfortunate choices."

“A teacher is a role model who should create a sense of security and guide students in their journey through education. The teacher is crucial for a learning environment that motivates and contributes to students' learning and development. This requires the teacher to show care for each student. It also involves helping students who make unfortunate choices [or] do not feel included […]. (Core curriculum, 3.5.)

On an individual level, prejudices and group hostility are driven by real needs for meaning, belonging, and influence over one's life (see ). Therefore, the teacher's ability to meet students with respect, provide them recognition, and facilitate equal interaction and genuine participation are essential prerequisites for prevention and creating room for change in attitudes.

“Teacher's ability to meet students with respect, provide them recognition, facilitate equal interaction, and genuine participation are essential prerequisites for prevention and creating room for attitude change.

Professional competence, therefore, involves not only knowledge and teaching methods but also how to detect and handle group-based offenses. These are challenges that teachers often find particularly difficult because they involve conflicting considerations. Teachers may face dilemmas when dealing with prejudiced statements or offensive behavior:

- How can the teacher fulfill the obligation to stop offenses, as Chapter 9A of the Education Act requires, while also showing care for all involved students?

- How should the teacher address prejudiced statements to show other students that these are not acceptable? Should she assert the school's position or take the student aside later for a calm conversation to avoid embarrassment in front of the whole class?

- How to set clear boundaries and simultaneously take seriously students' negotiating limits?

Behind such dilemmas lie fundamental pedagogical questions about setting boundaries and building relationships. To address these questions effectively, teachers need ethical awareness.

Ethical awareness is the ability to consider such dilemmas in light of fundamental ethical principles. Professional ethics in practice is about taking the time to think through these considerations, making ethically justified choices, and developing professional judgment. Reflections and considerations touch not only on the individual's "right" choices and actions in a specific situation but also point to overarching issues.

Thin vs. Thick Understanding of Professional Ethics

We can distinguish between a thin and a thick understanding of professional ethics. Hilde Afdal emphasizes that professional ethics in the thick sense: "does not only concern delimited dilemmas; it is also about having an ethical perspective on potentially everything that happens in kindergarten and school. Professional ethics is not just about acting correctly in situations but about being a good teacher and contributing to the development of a good kindergarten and school."

Within the comprehensive preventive work against prejudices and group hostility in schools, such a thick understanding of professional ethics means that challenges and dilemmas should be assessed with the school's value system as an ethical guide.

Furthermore, a thick understanding of professional ethics points to the frameworks that society and the institution set for professional practice. How does the school facilitate interaction and solidarity among students and groups of students? How do students' experiences of discrimination, varying socioeconomic status, or parental attitudes relate to conflicts and offenses that the teacher must handle? What do these factors mean for the teacher's choices and the need to find problem-solving strategies together with colleagues and/or management?

“How does the school facilitate interaction and solidarity among students and groups of students?

The Norwegian Union of Education's Ethical Platform (2012) distinguishes between three dimensions of professional ethics that also apply to work against prejudices, group hostility, and discrimination:

- The individual professional's responsibility in direct encounters with "their" kindergarten children or students and their parents.

- The individual professional's responsibility as part of the faculty at their workplace.

- The individual professional's responsibility as part of the teaching profession as a societal actor.

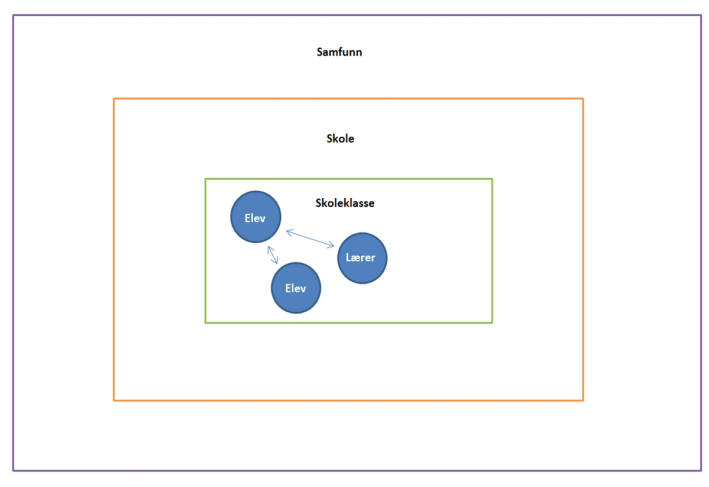

The platform thus connects professional ethics to micro- (individual/relationship), meso- (institution), and macro-levels.

Self-Reflection

A teacher's understanding of reality and interpretations, like everyone else's, is colored by their own background and experiences. These form the basis for the professional assessments and decisions the teacher makes all the time. Lack of awareness around this can contribute to misunderstandings and, in some contexts, unintended stigmatization or exclusion of students. For example, a teacher may speak to a student as a representative of a religion or country, attributing characteristics that the student does not identify with.

Professional ethical self-reflection for a teacher involves reflecting on the possibility that there are things taken for granted that may not align with the experiences of students or their parents with a different background.

“Teachers have a position and role in society that also involves power. The teacher makes the final decision about what to do in the classroom and is the one who should assess the students.

Both students and parents may feel that you, as a teacher, have a lot of power over the student's daily life and their future life course. This can challenge their sense of autonomy and control over their own lives. Parents may feel that you, as a representative of the government and a contact person for child protection services, also have power over their family situation and challenge their authority as parents.

Relational Awareness

The teacher needs ethical awareness of their own role as a "significant other" for the students. Being a teacher is a "moral" activity This means that teachers have a special responsibility towards students. The choices they make and their entire demeanor have a significant impact on the children and young people they teach and interact with.

The teacher should see and acknowledge each student as a unique and valuable human being. They should support the student in realizing his or her potential. Therefore, this dimension of professional ethics also involves being aware of one's own normative ideas and prejudices that may hinder seeing the student's needs and supporting the student's potential.

Relational awareness is not limited to the teacher-student relationship alone. In interactions with colleagues or parents, the teacher should also show recognition and respect, even in cases of disagreement or conflicting interests.

Institutional Awareness

Professional ethics is always practiced within a context, including the school's institutional frameworks, routines, and practices. These frameworks can either promote good, value-based choices or hinder them. Can rules and requirements that apply to everyone actually contribute to discrimination?

The school's premises or the lack of physical meeting points and arenas for interaction in the student group can lead to segregation and exclusion of certain students. How are the school's walls filled with life? Do common activities encourage interaction across existing friendship circles among students? And how is each student supported in becoming part of the community?

“Lack of physical meeting points and arenas for interaction in the student group can lead to segregation and exclusion of certain students.

Teachers' professional ethical competence also involves reporting to management about discrimination and exclusionary dynamics. Teachers must contribute to a joint effort to create a fair and inclusive school culture.

Social Awareness

“School does not operate in a vacuum; it is influenced by current debates and conflicts at the societal level and is marked by social inequality and structural discrimination.

A thick professional ethical awareness related to prejudices and group hostility cannot exist without an awareness of how structural racism, unquestioned norms, and racialized socio-economic inequality affect the daily life of the school.

What experiences of discrimination and exclusion do students have, and how can these experiences affect students' self-esteem and expectations of school? In what ways is the teacher's position related to privileges related to gender, social background, and skin color, and how does this affect interactions with students and parents? Here, professional ethics is linked to awareness of power and privilege.

A professional ethical social awareness also means that teachers develop an awareness of being agents of change, both as individuals and as part of a professional community.

Micro-, Meso-, and Macro-levels

So far, we have focused on different dimensions of a teacher's professional competence in dealing with mechanisms of '', and in school.

These mechanisms play out on a societal and institutional level, while being anchored in individual thought patterns, attitudes, and behaviors. Therefore, it is important for teachers to develop an awareness of these levels and how they interact in situations and events that occur daily in school. The diagram with the three levels depicted here can help analyze events where prejudiced attitudes and discriminatory practices are expressed. Analyzing where the problem can actually be "placed" can, for example, contribute to avoiding reactions that focus solely on the fact that an individual has done "something wrong."

An example:

In a staff room, a teacher states that a group of minority students "excludes themselves" at this school. Applying a micro-, meso-, and macro-perspective can help ask good questions and come up with better solutions. Such as in this example:

- Have minority students experienced exclusion before, either at this school or in other contexts?

- Can reaching out to each other provide recognition and security by avoiding the risk of exclusion?

- How can teachers contribute to ensuring that all students experience recognition and belonging?

- What can the teacher community do to facilitate positive interaction among students with different backgrounds?

A Professional Ethical Language

Anker et al. write, "Teachers are concerned with professional ethics but often lack a professional language for ethical issues. This can make it difficult to have good discussions within a faculty about issues involving professional ethical considerations and requiring practical solutions" (pp. 64–68).

The example in the previous section underscores this claim. Without a professional and professional ethical language that helps teachers "unpack" complex situations and challenging events, the likelihood increases that individual teachers or the school as an institution will resort to short-term, punishment- and sanction-based solutions. This leaves the deeper causes, including systemic ones, unresolved.

Literature

Afdal, H. (2014). Det gode og det rette i profesjonsutøvelsen. Et diskursanalytisk blikk på utviklingen av Lærerprofesjonens etiske plattform. I: Afdal, G., Røthing, Å., Schjetne, E. (red.). Empirisk etikk i pedagogiske praksiser: artikulasjon, forstyrrelse, ekspansjon. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

Anker, H., Afdal, N., Johannesen, E. Schjetne og G. Afdal (2016). Et språk for etikk: Læreres profesjonsetiske forståelser og praksis. I BEDRE SKOLE NR 2/2016

Hansen, D. (2001). Teaching as a moral activity. In V. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of research on teaching, 4th ed. (826–857). Washington, DC: AERA.